We’ve all seen cats climb up trees, scratch on posts, and claw up our furniture, but why don’t dogs exhibit such behaviors? When you think about it, dogs don’t seem to use their claws that much at all. What is so different between a cat’s paw and a dog’s paw that gives one a useful sharp tool, while the other is stuck with a blunt and ineffective appendage?

We’ve all seen cats climb up trees, scratch on posts, and claw up our furniture, but why don’t dogs exhibit such behaviors? When you think about it, dogs don’t seem to use their claws that much at all. What is so different between a cat’s paw and a dog’s paw that gives one a useful sharp tool, while the other is stuck with a blunt and ineffective appendage?

Taking a Closer Look at the Anatomy

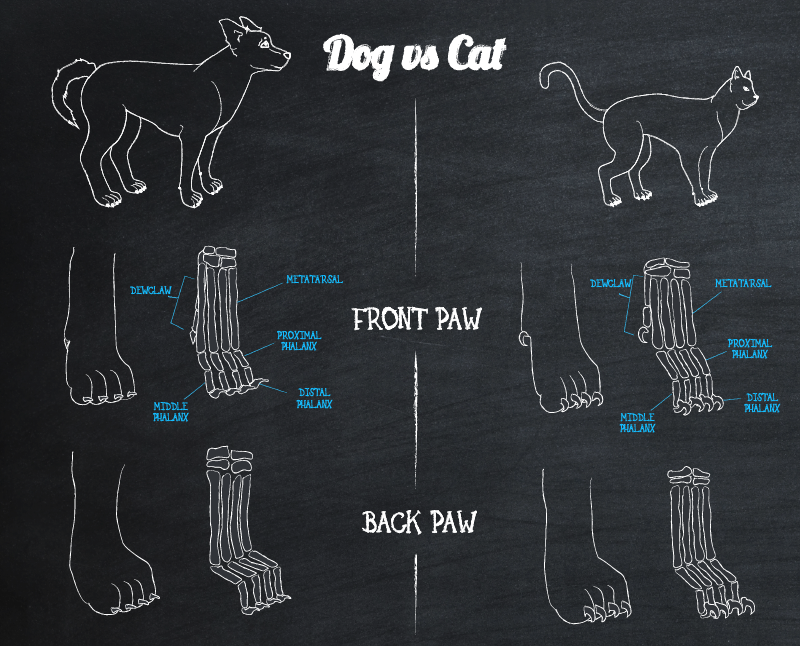

When comparing our pets’ feet, they seem to be very similar at first glance. Both dogs and cats are digitigrade, which means that they stand and walk with the heals up and only their toes touching the surface. Both species have four toes on their back paws and five toes on their front paws, one of which being the dewclaw – the smaller, seemingly functionless toe located more towards the inside of their front legs. An x-ray will show that their feet contain metatarsal bones connecting the ankle to the toes, and all of their toes (excluding the dewclaw) contains three bones – the distal, middle, and proximal phalanges that are connected to each other by an elastic fibrous tissue called a ligament, allowing the bones to shift and rotate in certain directions.

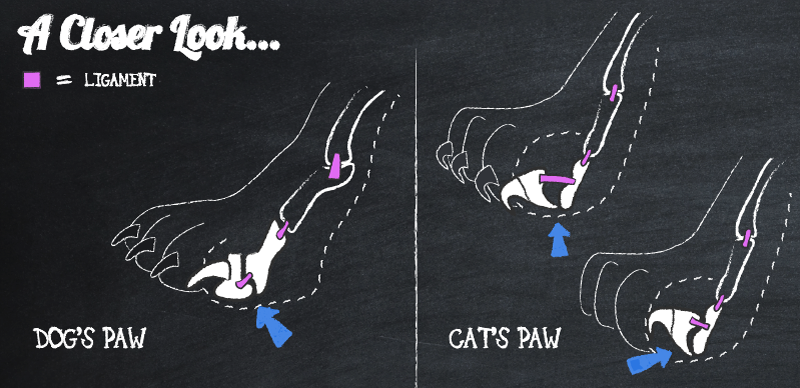

On closer inspection, the main difference can be found with the middle phalanx, where the dog has an even symmetrical shape while the cat’s are more asymmetrical. What may seem like a minor discrepancy actually creates a major contrast in functionality; The dog can only lift its distal phalanx back so far, but when the cat relaxes its muscles, their distal phalanx can be rotated back towards the middle phalanx, and essentially be tucked or “retracted” back into the paw. It is this retractable trait that protects the cat’s nails as they walk on various surfaces, keeping their claws nice and sharp. The dog on the other hand (among most digitigrade animals outside of the cat family) will develop blunt nails since their distal phalanx cannot retract and the tips are quickly worn down by whatever surfaces their feet interact with. Did you notice you can hear your dog’s nails tap on the wood floor as he walks while your cat seems to tiptoe around without making a peep?

Now the interesting question remains, how did this difference in anatomy come to be? Let’s take a look further into our pet’s ancestors and track the evolution of their lifestyle, their environment, and of course their paws.

NOTE ON DECLAWING: Cat claws are often clipped in an effort to defend our furniture from becoming filled with holes. The claws are made up of the protein keratin and are relatively painless to have cut (as long as the root vessels and nerves are avoided). But when it comes to declawing, that’s a whole different story.

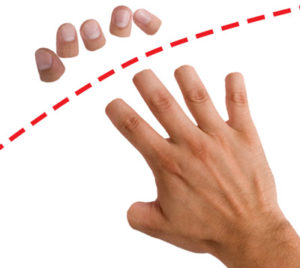

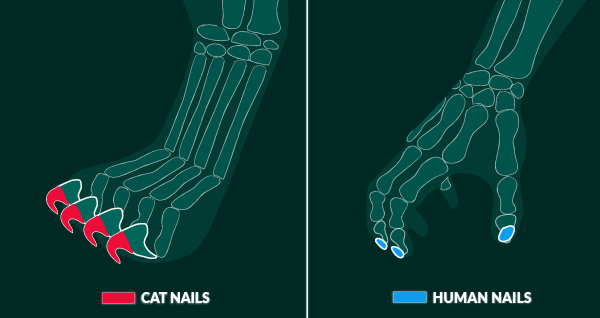

It may appear in the image above that the claw’s nails are growing directly out of the distal phalanges… that’s because they do. Unlike human fingernails, which are only connected to skin tissue, cat’s nails are connected directly to the bone. When it comes to declawing a cat, the entire distal phalanx – yes, an entire bone – must be removed with the nail (otherwise it would just grow back again). This would be the equivalent of amputating the tip of a human finger up to the first knuckle. And since cats solely walk on their toes, walking on the ends of their knuckles must be quite an unpleasant and painful way to live.

It may appear in the image above that the claw’s nails are growing directly out of the distal phalanges… that’s because they do. Unlike human fingernails, which are only connected to skin tissue, cat’s nails are connected directly to the bone. When it comes to declawing a cat, the entire distal phalanx – yes, an entire bone – must be removed with the nail (otherwise it would just grow back again). This would be the equivalent of amputating the tip of a human finger up to the first knuckle. And since cats solely walk on their toes, walking on the ends of their knuckles must be quite an unpleasant and painful way to live.

Evolution of Our Pet’s Feet Over Millions of Years

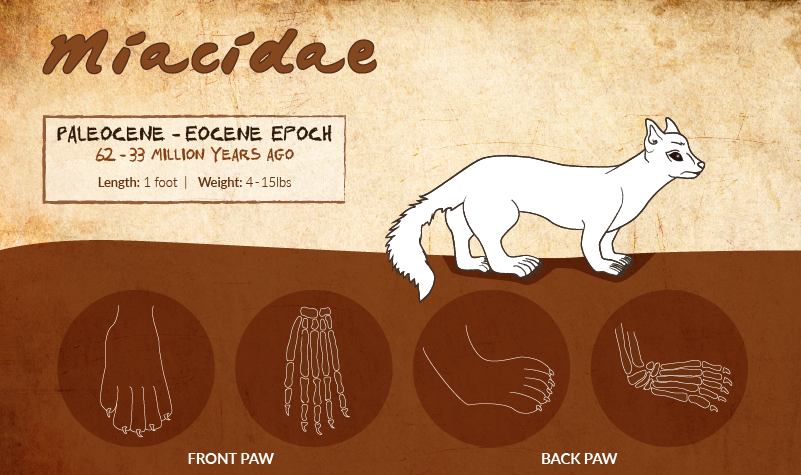

Earliest Ancestors – The Miacidae

Cats and dogs actually share the same ancestor, the Miacidae, dating back 62 millions years ago following the extinction of the dinosaurs. The Earth was a hot & humid place, encouraging the overgrowth of dense forests and tangled vegetation in a tropic-type settings. The Miacidae were small, weasel-sized mammals that mainly stayed in hiding, preferring to live amongst the treetops.

Looking more like a civet – dense fur, long tail, and pointy ears – the Miacids would spend their days climbing from tree to tree, using advanced stealth tactics to snatch up their prey (such as bugs and small rodents) from below before quickly climbing back up to avoid being seen by any nearby predators.

The Miacids’ small bodies soon adapted to accommodate their arboreal lifestyle. Their front paws had semi-opposable thumbs and sharp claws, allowing them to cling to almost anything. The set of five toes on both their hands and feet (similar to that of a racoon or kinkajou) would give them an extra grip on the bark.

The Caniformia-Feliformia Split

Far into the Miacids’ existence, the Carnivorans would emerge, a descending order of mammals that would soon split into two separate families – Canidae (dog-like creatures that would become ancestors to wolves, foxes, coyotes, jackals, and dingoes) and Felidae (cat-like creatures that would become ancestors to lions, tigers, panthers, pumas, and cheetahs) . While the Felidae (member, Felid) would go on to continue climbing trees and using their sharp claws, the Canidae (member, Canid) would take a different route and divide into three subfamilies: Hesperocyoninae, Borophaginae, and Caninae.

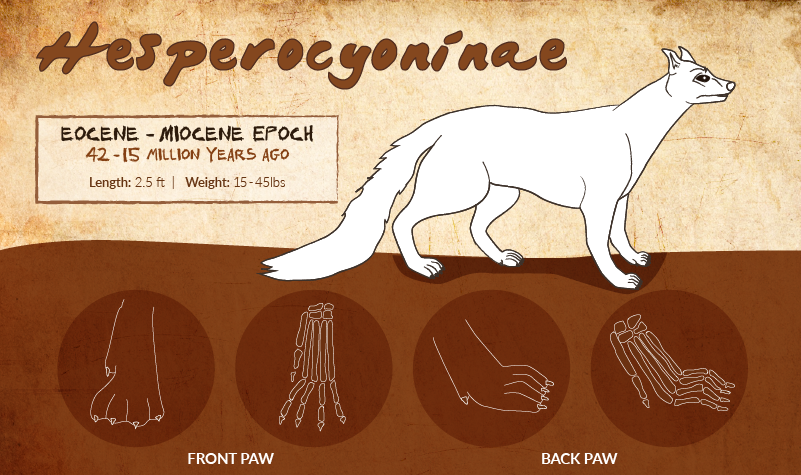

The Hesperocyoninae Explores Life on the Ground

The Hesperocyoninae was the earliest of the canids to evolve after the Caniformia-Feliformia split around 42 million years ago. They would experience a great shift in the Earth’s climate during their existence where the environment went from humid, dense forestry to a cooler, more open grassland. As less trees were accessible, the Hesperocyoninae began to explore life on the ground – here the canid would evolve yet again.

The Hesperocyoninae would grow to be about the size of a coyote, and their longer legs gave them the ability to cover more land in a shorter amount of time compared to its former counterpart. To help them run faster, their feet would become slightly digitigrade, but still retain a well developed first digit (thumb and big toe), although shorter than before.

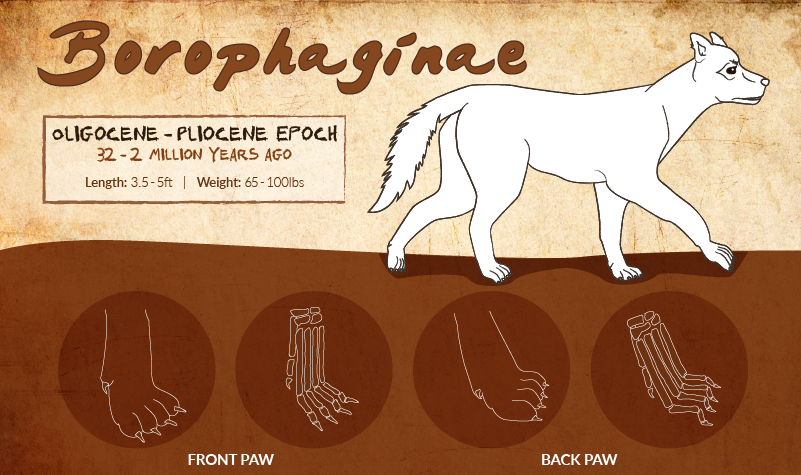

Borophaginae Nicknamed the “Bone-crushing dogs”

Around ten million years after the introduction of the Hesperocyoninae, would be the larger, more powerful canid known as the Borophaginae. About the size of the modern wolf, these canids were all about traversing great distances on the ground. Their long legs and muscular bodies allowed them to run fast for long periods of time, soon coming together in packs in order to take down larger prey. They were now fully digitigrade, running on their toes; Their fifth toe on the front feet could no longer reach the ground and the fifth toe on their rear feet was beginning to disappear and bore a similar resemblance to the dewclaws we see on our pups’ front feet today.

Although they could no longer use their blunt nails to attack, they were given the nickname, “bone-crushing dogs”, as they could take down their prey with a single bite.

These massive creatures became a top predator in the North American region, weighing up to 100 pounds and able to tackle horse-size mammals ten times it’s own size!

Caninae (and the Modern Dog)

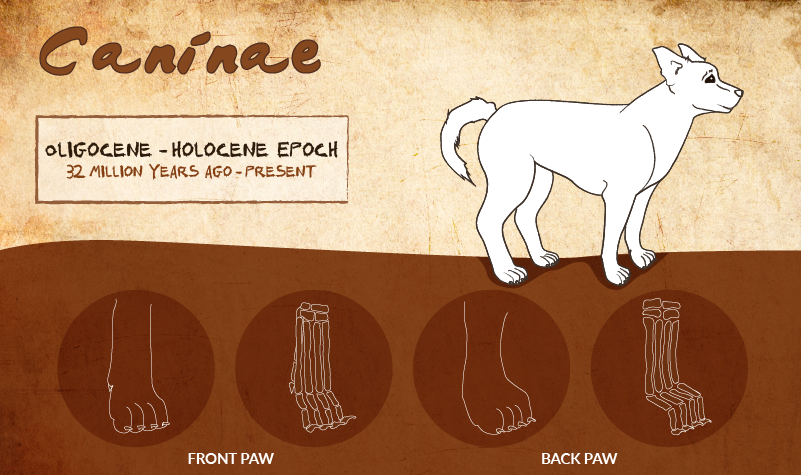

The final subfamily of canids were the Caninae, representing dog-like mammals from 32 million years ago up to and including the species that are alive today (including the dog).

When looking at all dogs as a whole, they have the most diverse set of breeds compared to any other species, however the basic anatomy remains the same.

The big toes that were on the back feet are now completely gone leaving only 4 toes on each paw, while each front foot bears fours toes with an additional small dewclaw near the wrist. Like any dewclaw, these toes have little bone and muscle structure, and is simply leftover osseous tissue as a result of the canid’s evolution.

Dogs have come a long way since their ancient predecessors, and although certainly less savage than they were before, they still retain many physical traits that helped them survive in the wild so many years ago.

Although dogs will occasionally use their dewclaws to help balance objects, their exact utility is pretty limited. The claw tends to grow in a curve and if left unclipped, it can get embedded into the pad of the paw. In some cases, a veterinarian might recommend to surgically remove the dewclaw to avoid an accidental tear that could cause a lot of pain to the dog later on. Although if not necessary, it is best to leave the dewclaw in place as it can help with stabilizing the wrist joint and help prevent arthritis as your dog ages.

Although dogs will occasionally use their dewclaws to help balance objects, their exact utility is pretty limited. The claw tends to grow in a curve and if left unclipped, it can get embedded into the pad of the paw. In some cases, a veterinarian might recommend to surgically remove the dewclaw to avoid an accidental tear that could cause a lot of pain to the dog later on. Although if not necessary, it is best to leave the dewclaw in place as it can help with stabilizing the wrist joint and help prevent arthritis as your dog ages.

How is a Dog’s Sense of Smell Different from Ours… and Why?

How is a Dog’s Sense of Smell Different from Ours… and Why? What are those little balls of poop? Identifying Local Wildlife Dung.

What are those little balls of poop? Identifying Local Wildlife Dung. Top 5 Dog Superstitions with Possible Explanations

Top 5 Dog Superstitions with Possible Explanations